The Hidden Cost of Efficient Learning

Is the pursuit of efficiency in digital learning inadvertently creating a hidden cost? My latest blog post, "The Hidden Cost of Efficient Learning," explores why active, effortful learning is more critical than ever in the age of digital media and AI.

This isn't about rejecting technology, but repositioning it. Join the conversation on how we can design learning experiences that restore curiosity, agency, and deep understanding.

Why Active Learning Matters More in an Age of Digital Media and Generative AI

Teachers are seeing polished essays that students cannot explain. Parents watch children complete assignments in minutes, yet struggle to articulate their thinking. The work looks finished, but learning feels hollow. Policymakers worry about equity, ethics, and what gets lost when efficiency becomes the priority.

Researchers warn that while AI can increase efficiency, it may also reduce the very cognitive effort that learning depends on. The problem is not that students are lazy, unmotivated, or incapable of thinking deeply. The problem is that many digital learning environments change expectations about what learning feels like, and, in doing so, reshape how learners engage with it.

Learning Was Never Meant to Be Passive

For years, education treated students like empty vessels to be filled (behaviorism). But theorists like Piaget argued that we don't just absorb knowledge; we construct it. Learners don’t simply take knowledge in; they build it by testing ideas, encountering contradictions, and reorganizing their thinking.

From this perspective, learning depends on disequilibrium, the experience of realizing that what you currently understand is no longer sufficient. This cognitive tension can feel uncomfortable, but it is not a flaw in the process; it is the engine that drives it.

When new information fits easily with what we already believe, we assimilate it. Learning feels smooth. But when it doesn’t fit, accommodation is required. Understanding must change. That process is effortful, slow, and uncomfortable.

In other words, active learning assumes that learners play a role in their own learning. They question, struggle, revise, and persist. In this model of learning, curiosity and critical thinking are central to how learning happens.

Digital Media and AI Default Toward Passive Learning

Digital tools and AI aren’t necessarily designed to undermine active learning. But many of their core design features unintentionally do so. For example, most digital platforms are optimized for speed, clarity, and completion.

In this model, confusion is treated as a problem to fix, rather than an essential part of the learning process. Frustration is minimized. Answers arrive immediately. Progress is measured by finishing rather than transforming understanding.

These features of digital media and AI are incredibly effective for access and convenience. They are less effective for learning that requires exploration, uncertainty, and revision.

When a learner encounters difficulty, AI resolves it almost instantly. Explanations are fluent, organized, and confident. The system restores a sense of clarity before the learner has had to grapple with the mismatch or disequilibrium that would have motivated deeper understanding.

Over time, this subtly trains a passive learning stance:

uncertainty becomes something to avoid

curiosity feels unnecessary

effort feels inefficient

struggle feels like failure

This helps explain why students may appear engaged but struggle to explain their thinking, why work looks polished but understanding is thin, and why confidence collapses when support is removed.

The issue isn’t the tool. It’s the learning approach the environment encourages.

Why Curiosity and Critical Thinking Take the Hit

Curiosity thrives when learners are allowed to linger in questions. Critical thinking requires time, cognitive space, and tolerance for ambiguity.

Digital environments, and especially AI-supported ones, often remove those conditions.

When confusion disappears quickly, learners have fewer opportunities to ask:

Why doesn’t this make sense yet?

What am I missing?

How does this connect to what I already know?

Instead, learning becomes something that happens to students rather than something they actively do.

This aligns with what many parents and teachers report: students are completing tasks quickly but struggling to reason, explain, or transfer knowledge. From a developmental perspective, this is not surprising. Critical thinking isn’t simply a skill to be practiced; it’s a cognitive state that requires attention, emotional regulation, and the willingness to stay with uncertainty.

When environments consistently reward fast resolution, the brain learns to escape discomfort rather than engage with it.

A Concrete Example

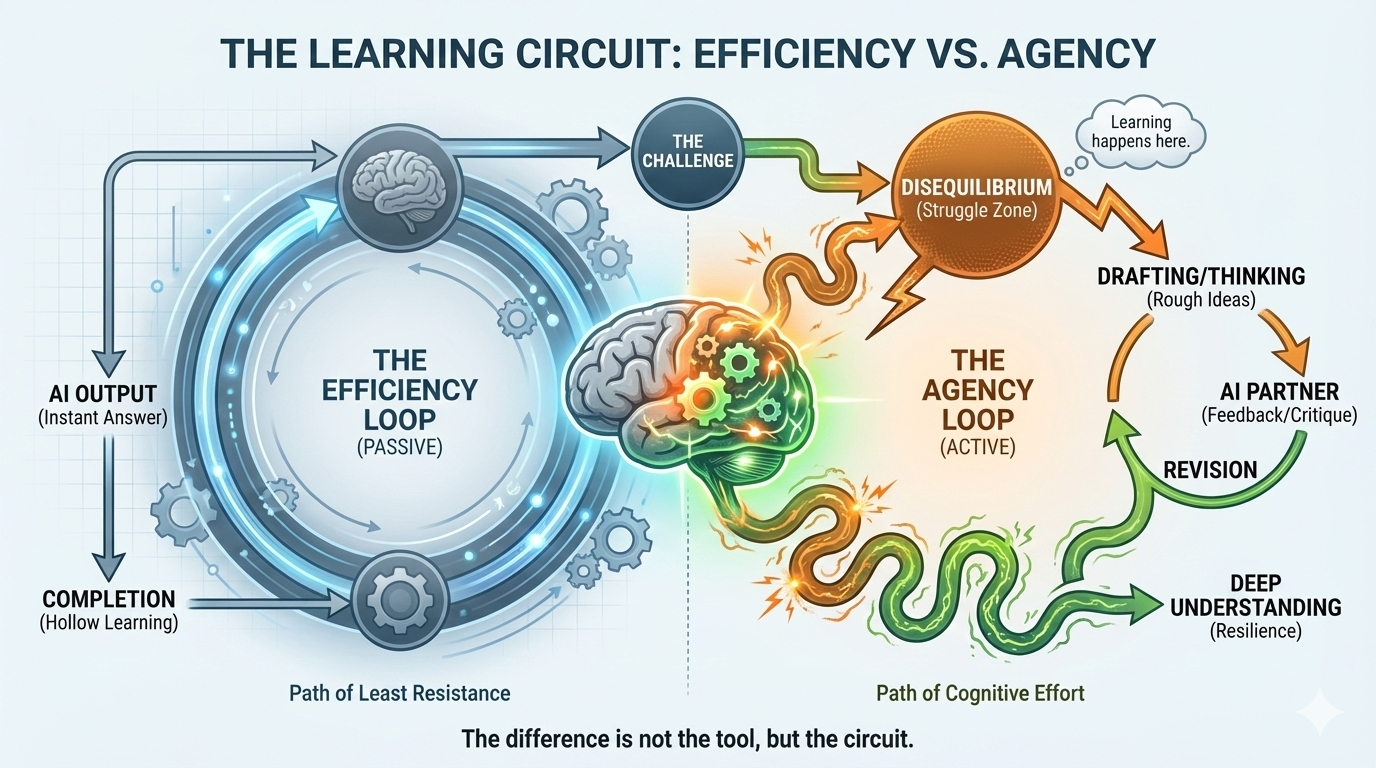

Consider a student writing an essay or solving a complex problem. The outcome depends entirely on the loop they choose.

🔴 The Passive Loop

Optimized for speed and completion.

Immediate Input: The student inputs the prompt into AI immediately.

External Thinking: The tool generates the outline, arguments, and structure.

Frictionless Edit: The student polishes the language without grappling with the logic.

Outcome: The work looks finished, but the learning is hollow. The student struggles to answer follow-up questions.

🟢 The Active Loop

Optimized for curiosity and retention.

The Pause: The student sketches ideas or attempts a first draft before opening any tools.

Productive Struggle: The student encounters "disequilibrium" (confusion) and tries to resolve it manually.

AI as Partner: AI is brought in late to ask: "What did I miss?" or "Critique my argument."

Outcome: The process is slower, but the knowledge belongs to the student. They can explain and defend their thinking.

While the Efficiency Loop prioritizes speed, the Agency Loop prioritizes understanding.

The same pattern appears in mathematics. A student asks ChatGPT how to solve for x. The tool shows the steps. The student copies them. But when the equation changes slightly, they're lost, because they never wrestled with why those steps work.

In an active learning loop, the student struggles first. They sketch ideas, encounter contradictions, feel uncertain, and revise. AI may still be used, but later, to challenge assumptions, generate counterarguments, or test clarity.

The difference is not whether AI is used. The difference is when and how it enters the learning process.

What to Do Instead: Restoring Active Learning in a Digital Age

If the problem is not learners’ capacity, but the conditions surrounding learning, then the response is not to remove technology. It is to design learning experiences that restore agency, curiosity, and productive struggle, while using digital media and AI in ways that support, rather than replace, the work of thinking.

Here are practical ways parents and teachers can do that.

Use AI to Extend Thinking, Not Replace It

AI is most powerful when it enters after thinking has begun, not before it has started.

What this can look like in practice:

Write first, AI second. Ask students to write an explanation, solution, or argument in their own words first.

Gatekeep the tool. Only then invite AI into the process.

What this avoids:

Zero-draft generation: Asking AI to generate the answer from scratch.

Uncritical acceptance. Treating AI output as finished understanding.

Helpful AI prompts that support active learning:

“What assumptions might I be making here?”

“What’s a reasonable counterargument to my position?”

“Where might my explanation be unclear or oversimplified?”

“What would someone who disagrees with me say?”

Used this way, AI becomes a thinking partner that challenges, stretches, and refines ideas rather than replacing the work of construction.

Slow the Moment of Resolution

Digital tools are excellent at resolving confusion quickly. Active learning often requires the opposite. When a learner is confused, resist the impulse to immediately clarify, search, or generate an answer.

What this can look like in practice:

Articulate the confusion. Before Googling or asking AI, ask the learner to write or say what doesn’t make sense yet.

Implement a waiting period. Encourage a short pause: “Let’s sit with this for two minutes before we look anything up.”

How digital tools can help (without short-circuiting learning):

Create a ‘confusion log’. Use a notes app or shared doc where students record “what I think so far” and “what’s confusing me” before seeking help.

Pinpoint the friction. Have students highlight or comment on the exact sentence, graph, or idea that triggered confusion before moving on.

This keeps disequilibrium alive long enough to motivate deeper thinking instead of erasing it immediately.

Make Curiosity the Goal, Not Just the Outcome

AI-mediated learning often rewards completion. Active learning rewards inquiry. Shift attention toward the quality of questions learners are asking, not just the answers they produce.

What this can look like in practice:

Reward high-quality inquiry. Praise questions like: “Why does this work here but not there?” or “What would happen if…?”

Require a lingering question. Ask learners to submit one open question along with completed work.

How digital tools can help:

Maintain a ‘parking lot’. Use shared documents, discussion boards, or classroom platforms to maintain a running list of “questions we’re still thinking about.”

Track the evolution. Encourage students to revisit and revise questions over time as their understanding grows.

This teaches learners that curiosity is not a detour from learning; it is learning.

Make Struggle Visible

Many learners interpret difficulty as failure because learning environments rarely name struggle as part of the process. Adults can change this by narrating the learning process out loud and making the invisible work of thinking more visible.

What this can sound like:

“This is usually the part where people feel stuck.”

“If this feels uncomfortable, it often means your thinking is changing.”

“This confusion is doing important work.”

Why this matters in digital environments:

When AI or digital tools make learning feel smooth and immediate, students may assume struggle signals incompetence. Naming struggle reframes it as evidence of growth rather than deficiency.

How digital tools can help:

Capture the messy middle. Use shared documents or learning platforms to capture drafts, revisions, and false starts, not just final products.

Self-annotate the struggle. Encourage students to annotate their own work with comments like “This part felt confusing” or “I changed my mind here.”

Review version history. Use version history or screen recordings to show how ideas evolve over time, making the struggle visible rather than hidden.

Use AI as a mirror. Ask students to use AI reflectively by asking it to identify where an explanation might still be unclear, reinforcing that learning is iterative.

When struggle is documented and preserved rather than edited out and erased, learners begin to see it as a normal and necessary part of learning rather than something to avoid.

Interrupt Avoidance Gently

When learners disengage at the first sign of difficulty, the goal is persistence, not pressure.

What this can look like in practice:

“Explain it one more time in your own words before checking.”

“Try one more example before we bring in support.”

“What’s one small step you could take next?”

How digital tools can support this:

Allow ‘rough’ formats. Use voice notes, screen recordings, or drafts so learners can externalize partial thinking without needing a polished answer.

Assign iterative milestones. Encourage iterative submissions rather than one final product.

Small moments of persistence rebuild tolerance for effort over time.

Protect Unfinished Learning

Digital environments push toward closure, but learning often benefits from leaving ideas open.

What this can look like in practice:

Circle back. Revisit an earlier misconception weeks later and ask, “How do you think about this now?”

Leave loose ends. End discussions with: “What are we still unsure about?”

How digital tools can help:

Map the journey. Maintain evolving notes, timelines, or concept maps that show how understanding changes over time.

Visualize the progress. Use version history or saved drafts to make learning visible, not just final answers.

This teaches learners that learning unfolds gradually and that not knowing yet is a legitimate, productive state.

From Efficiency to Agency

None of these practices rejects digital media or AI. They reposition them.

They shift technology from:

answer provider → thinking partner

efficiency engine → reflection tool

clarity machine → curiosity amplifier

When learners are supported in staying with uncertainty, asking better questions, and using tools to extend, and not to replace their thinking, active learning becomes possible again, even in technology-rich environments.

Keeping Humans in the Learning Loop

Digital media and AI can support learning, but only when humans remain actively involved. Teachers, parents, and learners themselves provide something technology cannot: context, judgment, and relational feedback.

Active learning depends on agency. Curiosity depends on permission to not know yet. Critical thinking depends on time and cognitive space.

When we restore those conditions, learning regains its depth, not by rejecting technology, but by using it in ways that preserve the work of thinking.

This approach requires intention. It means designing learning experiences that feel slower and messier than what AI makes possible. But when we do this work, and when we keep humans actively engaged in the learning loop, we preserve not only knowledge acquisition but the curiosity, agency, and resilience that make lifelong learning possible.

AI Didn’t Break Learning, It Changed What Learning Feels Like

Digital media and AI promise clarity, speed, and effortless learning. But real learning has never worked that way. This article explores how AI reshapes what learning feels like—and why struggle, confusion, and effort still matter for deep understanding.

Why Effortless Learning Comes at a Cost

Digital media and AI tools deliver explanations with unprecedented speed and fluency. Confusion rarely lasts long. Uncertainty is quickly resolved. For learners, this can create the impression that learning should feel clear, efficient, and complete.

That impression is increasingly reinforced by companies promising effortless learning with tools that claim to optimize studying, eliminate struggle, and help students achieve top grades with minimal effort. The message is subtle but powerful: if learning feels hard, you’re doing it wrong.

But learning has never worked that way.

Real understanding develops through moments of uncertainty, revision, and effort. It often feels slower just as it starts to deepen. Confidence wavers before it stabilizes. Progress moves forward, then circles back.

What has changed is not how learning works, but the environments shaping what learners expect it to feel like.

Learning is non-linear

From a developmental perspective, learning is not the steady accumulation of information. It is a process of reorganization driven by moments of imbalance.

New ideas don’t simply add themselves to what we already know. Sometimes they fit easily. When they do, understanding feels stable, and effort is minimal. But other times, new information exposes gaps, contradictions, or limits in what we thought we understood. When that happens, the system becomes unsettled. Psychologist Jean Piaget described this state as disequilibrium.

Disequilibrium is the experience of realizing that something no longer quite makes sense. It is the cognitive tension that arises when existing ideas fail to fully explain what we are encountering. Importantly, this tension is not a problem to eliminate. It is the motivation that drives learning forward.

When understanding remains in balance, there is little reason to change. It is only when that balance is disrupted that the mind becomes motivated to adapt.

If new information can be absorbed without altering existing ideas, we assimilate it. Learning feels smooth and efficient. But when assimilation fails, the only way to restore balance is through a process called accommodation, by revising how we understand the world. That process is slower, effortful, and often uncomfortable.

Confusion, hesitation, and even temporary drops in performance are common signs that accommodation is underway. These moments are not evidence of inability. They are signals that understanding is being actively rebuilt.

Digital media flattens the learning experience

Online platforms are designed to feel clear, efficient, and continuously progressive. Information is broken into clean segments. Explanations arrive quickly, and progress is marked by completion rather than transformation.

These environments are highly effective at supporting early stages of learning, such as simple exposure, recognition, and basic understanding. They help learners encounter ideas, hear explanations, and develop familiarity. But deeper learning requires something different.

Deep learning requires applying ideas in unfamiliar situations, comparing perspectives, identifying limitations, and integrating new information with what is already known. These processes are often slow and unpredictable; they involve uncertainty, revision, and moments of doubt. They do not move neatly from one step to the next.

When learning environments emphasize speed and clarity, they create the impression that learning itself should feel smooth. When it doesn’t, learners are left to interpret the mismatch on their own.

Where AI fits into this picture

The rise of AI has brought many of these issues to the fore. Concerns about artificial intelligence in education often focus on misuse, students outsourcing work, bypassing effort, or relying too heavily on automated tools. Those concerns are understandable, but they miss a deeper issue.

The most significant impact of AI on learning is not that it provides answers, but that it resolves uncertainty too quickly. AI systems are exceptionally good at producing fluent explanations, polished summaries, and confident responses. The language is clear, the structure is sound, and the output looks finished. But clarity is not the same as comprehension.

From a developmental perspective, learning depends on disequilibrium, the moment when existing understanding is no longer sufficient. That cognitive tension is what pushes learners to question, revise, and reorganize their thinking. Without it, there is little motivation for learning to deepen. AI can interrupt this process by restoring a sense of equilibrium too early.

When an AI-generated explanation immediately smooths over confusion, learners may never fully experience the mismatch that would have driven accommodation. The system feels settled again, but understanding has not necessarily changed. The appearance of resolution replaces the work of reconstruction, making deep, transferable learning less likely to occur.

Over time, this can subtly reshape expectations. If learning consistently feels clear and complete, difficulty begins to feel like an error rather than an invitation to think. When challenges arise without AI support, they are more likely to register as failure rather than as a normal and necessary part of learning.

None of this means AI has no place in education. Used thoughtfully, it can extend thinking, offer alternative perspectives, and support reflection. The risk lies not in the tool itself, but in the way it can short-circuit disequilibrium and resolve uncertainty before learners have had a chance to learn from it.

When learning feels wrong, identity takes the hit

Developing learners are not just acquiring knowledge; they are forming beliefs about themselves as learners. They are constantly, often implicitly, asking questions like: Am I good at this? Do I belong here? What does it mean when this feels hard?

When difficulty arises in environments that suggest learning should be easy and linear, struggle is misinterpreted. Instead of thinking, This is challenging because I’m learning something new, learners are more likely to think, This is challenging because I’m not good at this.

Over time, this interpretation starts to erode persistence. Effort begins to feel like evidence against ability rather than a pathway toward it. Learners disengage not necessarily because they lack capacity, but because the experience of learning no longer matches what they have been taught to expect.

The problem isn’t effort, it’s expectations

When confusion or difficulty arises, digital environments offer immediate relief. Answers arrive quickly. Explanations smooth things over. Discomfort disappears. Over time, this creates a powerful learning loop: effortful struggle becomes something to escape, and rapid resolution becomes something to seek.

This pattern is quietly reinforced. Avoiding difficulty feels better in the moment, so it is more likely to happen again. The nervous system learns that confusion is a signal to disengage or outsource rather than to persist. What looks like low motivation is often a well-learned response to environments that reward escape over endurance.

Digital environments, and increasingly AI-supported ones, excel at delivering information quickly and clearly. What they struggle to convey is the value of confusion, revision, and slow understanding. When those elements are minimized, learning may feel more comfortable in the short term, but less durable in the long term.

This helps explain why learning can feel easier to access yet harder to sustain. The conditions that support deep, lasting understanding are replaced by conditions that reward immediate relief.

None of this means that digital learning, or AI, should be rejected. It does mean that we need to be more intentional about the expectations we set around learning.

Learning has never been smooth or predictable. It is effortful, uneven, and occasionally frustrating. Those experiences are not obstacles to understanding; they are part of how understanding is created.

When learners are supported in expecting confusion, tolerating pauses, and persisting through difficulty, learning regains its depth. Capacity does not need to be rebuilt. It is already there.

What needs rebuilding is our shared understanding of what learning actually looks like. If environments shape what learners avoid, they can also be redesigned to shape what learners practice.

Restoring the conditions for learning

If the problem is not capacity, but conditions, then the response is not to remove technology or demand more effort. It is to deliberately restore the experiences that learning depends on.

That starts with making room for productive discomfort again.

Here are some practical strategies that can begin to rebuild true learning:

Slow the moment of resolution.

When students encounter confusion, resist the impulse to immediately clarify or optimize it away. This might mean asking, “What part doesn’t make sense yet?” before offering help, or encouraging a learner to sit with a question for a few minutes before searching for an answer. The goal is not frustration, but familiarity with uncertainty.Use AI to extend thinking, not replace it.

AI is most helpful after learners have struggled, not before. For example, instead of asking an AI to generate an answer, students can be prompted to explain their current understanding first, then use AI to compare, critique, or refine it. This preserves disequilibrium while still benefiting from support.Make struggle visible and expected.

Teachers and parents can model this explicitly: “This part is usually where people get stuck,” or “If this feels confusing, that’s a sign you’re doing real work.” Naming the struggle as normal reduces the urge to escape it.Interrupt avoidance loops.

When learners habitually disengage at the first sign of difficulty, the response doesn’t need to be forceful. It can be as simple as encouraging one more attempt, one more question, or one more explanation in their own words before moving on. Small moments of persistence rebuild tolerance.Shift what counts as progress.

Progress does not always look like completion. It can look like better questions, clearer explanations of confusion, or more precise use of language. When these are recognized, learners begin to associate effort with growth rather than failure.Protect spaces where learning stays unfinished.

Not every problem needs an immediate answer. Leaving discussions open, returning to ideas later, or revisiting earlier misunderstandings teaches learners that learning is something that unfolds over time, not something that must be resolved instantly.

None of these practices eliminates efficiency or support. They simply rebalance it. They allow learners to start to experience confusion without panic, effort without shame, and difficulty without withdrawal.

From Discomfort to Escalation: What Happens When Social Regulation Fails Online

Online interactions often escalate not because people have changed, but because the systems that normally regulate social behavior are weakened or missing. When emotional cues disappear and speed increases, misunderstanding grows, regulation strains, and conflict becomes more likely, especially for developing minds.

If you’ve spent any time online, you’ve likely seen how quickly interactions can escalate. Comments that might feel neutral in person often feel harsher online, and minor misunderstandings can become personal disputes in just a few exchanges. Disagreement sharpens faster, patience wears thinner, and conversations that start casually can suddenly feel charged.

Because this pattern is so common, it’s easy to assume it reflects a change in people themselves, that people are simply ruder online, or that digital spaces bring out the worst in us. But developmental science suggests a different explanation.

Last week, I wrote about why social skills can feel harder to practice in today’s environments. This post focuses on what happens next, when the systems that normally regulate social interaction begin to fail.

Social Regulation Usually Works Quietly

In face-to-face interaction, social regulation happens mostly in the background. We notice confusion on someone’s face and hesitate. We soften our tone when we see hurt. We pause when we realize our words landed differently than we intended.

These moments aren’t mistakes; they are regulatory signals. Discomfort plays an important role in this process, prompting recalibration when clarification, apology, or adjustment is needed.

Most of the time, we don’t notice this system at all; we only notice it when it’s missing.

What Changes Online

Online interaction alters this regulatory system in important ways.

First, it lowers the cost of avoidance. Conversations can be ended quickly. Conflict can be delayed or bypassed. Repair becomes optional rather than expected.

Second, even when people do engage, many of the signals that support regulation are weakened or absent. Facial expressions are missing or delayed. Tone is flattened. Timing cues are harder to read. Emotional reactions are less visible.

This doesn’t make interaction emotionally neutral. It makes it more ambiguous, and ambiguity places greater demands on the brain.

When Emotional Cues Disappear, Regulation Strains

In face-to-face interaction, much of social understanding happens automatically. The brain integrates facial cues, tone, posture, and timing with little conscious effort.

When those cues are missing, interpretation becomes more difficult. Instead of reading emotion directly, people must infer it. Was that sarcastic or serious? Are they upset or just brief? Did I say something wrong?

This interpretive effort increases cognitive load, pulling resources away from emotional regulation, perspective-taking, and thoughtful response. Under load, the brain fills in gaps quickly, and often defensively.

Ambiguity is more likely to register as a threat or rejection, especially for children and adolescents whose regulatory systems are still developing. When regulation is strained, escalation becomes more likely, not because people intend harm, but because the system is operating closer to its limits.

Speed Turns Strain Into Escalation

Digital interaction also moves quickly. Messages are sent and received in rapid succession, often without time for emotional settling or reflection.

In face-to-face interaction, hesitation is built in. Online, hesitation has to be chosen.

When speed combines with cue loss and increased cognitive load, the space for recalibration shrinks. Misinterpretation compounds. Emotional responses arrive before regulation has time to catch up.

When Critical Thinking Gives Way to Defense

One of the clearest signs of regulatory breakdown online is not just escalation, but a shift in how people argue. In comment sections and online debates, disagreements often move quickly from ideas to identities. Arguments are supported not with evidence, but with insults, dismissals, or attacks on character. People say things they would rarely say face-to-face.

This is often described as a lack of critical thinking. But from a developmental perspective, that framing misses something important.

Critical thinking is not just a skill. It is a state.

It depends on available cognitive resources, emotional regulation, time, and a tolerance for ambiguity. When people feel calm and unthreatened, they are far more capable of weighing evidence, considering alternative perspectives, and staying with complexity.

Online environments often remove those conditions. High speed, reduced emotional cues, public visibility, and identity threat all increase cognitive and emotional load. Under these conditions, the brain shifts from evaluation to protection.

An ad hominem attack is an argument that targets the person rather than the idea, questioning intelligence, motives, or character instead of engaging with evidence. In this context, these attacks aren’t reasoned arguments; they’re defensive shortcuts. Attacking the person feels faster and safer than engaging with the idea, especially when repair feels unlikely and social feedback is muted.

What looks like a collapse of critical thinking is often a predictable outcome of interaction under threat.

Why This Matters for Development

If last week’s post focused on how social skills develop through practice, this section focuses on what happens when the conditions for that practice break down.

Children and adolescents learn how to regulate social interaction by practicing it under real conditions, not by being told what to do.

Regulation develops through repeated experiences of navigating uncertainty, reading emotional feedback, tolerating discomfort, and repairing missteps. Each of these moments teaches the nervous system something about pacing, accountability, and recovery.

When those regulatory conditions are consistently weakened, either through avoidance, cue loss, or high-speed interaction, young people get fewer opportunities to practice regulation. Over time, interaction can begin to feel more reactive than reflective, not because capacity has diminished, but because the balance of practice has shifted.

This does not mean children and adolescents are fundamentally less empathetic, less thoughtful, or less capable than previous generations. The underlying capacity remains. What has changed is the environment in which that capacity is exercised.

What Adults Can Do When Regulation Is Failing

Conflict is a normal and necessary part of development. The goal is to restore the conditions that support regulation, repair, and learning.

Slowing interaction when the stakes are high can help regulation catch up. Encouraging pauses, unsent drafts, or brief breaks before responding gives the nervous system time to settle.

Moving important conversations off text matters. Conflict, clarification, and repair are far easier when emotional feedback is available. Text is efficient, but emotionally incomplete.

Modeling repair out loud shows children how regulation works in real time. Statements like “That came out sharper than I meant” or “Let me try that again” teach that missteps are not failures, but opportunities to recalibrate.

Normalizing discomfort instead of eliminating it helps build tolerance. Staying nearby, offering reassurance, and encouraging one more moment of engagement teaches that discomfort is survivable and temporary.

Protecting face-to-face time provides irreplaceable practice. Unstructured, low-pressure interaction allows young people to read cues, manage uncertainty, and repair misunderstandings in ways digital spaces cannot fully replicate.

From Escalation Back to Understanding

The problem with online interaction isn’t that people have lost empathy, self-control, or the ability to think. It’s that many digital environments remove the signals that help regulate emotion and behavior, and when regulation fails, escalation follows.

The solution isn’t abandoning digital communication or returning to an idealized past. It’s being intentional about restoring the conditions that allow people, especially developing ones, to move through discomfort without threat and disagreement without collapse.

When those conditions are restored, regulation returns, and escalation becomes far less likely.

Are Children’s Social Skills Disappearing?

Are children losing their social skills—or are they getting fewer chances to practice them?

Social skills don’t disappear. They develop, or stall, based on experience. In a world where discomfort is easier to avoid and interaction is increasingly mediated by screens, many children are simply under-practiced. This article explains what developmental psychology tells us about social learning, why the real change is practice rather than capacity, and how parents and educators can support social growth at every age.

Why the Real Change Is Practice, Not Capacity

One of the most common concerns I hear from parents, teachers, and clinicians right now is that many children and adolescents are struggling socially.

Some fear that children are losing social skills altogether. But before we assume that social ability is disappearing, it’s worth asking a more precise developmental question: What kinds of social experiences are children getting to practice?

Social Skills Are Central to Human Development

Long before schools, writing, or technology, human survival depended on cooperation, trust, emotional attunement, and the ability to read others accurately. Our ancestors needed to detect threats, infer intent, and coordinate action within small, interdependent groups.

Our brains didn’t evolve primarily to solve abstract problems; they evolved to read people.

Social cognition, or interpreting facial expressions, tone of voice, posture, and emotional shifts, is foundational to how humans navigate the world. And like any complex system, it develops through experience.

Reading Faces Comes Before Reading Words

One of the earliest and most powerful human abilities is reading emotion from faces.

Infants don’t need language to understand emotional meaning. Through a process known as social referencing, babies look to caregivers’ facial expressions to decide how to interpret unfamiliar situations. Is this safe? Is this dangerous? Is this something to approach or avoid?

Across thousands of these moments, children learn how emotions work, including how they appear, change, and resolve.

These early experiences are supported by secure attachment. When caregivers provide consistent emotional signals and predictable responses, and when children feel safe to explore the world both physically and socially, children learn that emotions, even uncomfortable ones, are manageable. This supports emotional calibration, empathy, and social confidence.

Social Interaction Has Always Included Uncomfortable Situations

Face-to-face interaction often includes uncertainty, silence, missteps, and emotional risk. These moments are not developmental failures. They are the training ground for developing social skills.

I sometimes joke that my kids will never know the sheer terror of calling a girl’s house and having to talk to her father before I could talk to her. And it really was terrifying. You assumed the person on the other end of the line didn’t like you. Your voice tightened. You rehearsed what you were going to say. You stumbled through it anyway. And you stayed on the line because hanging up wasn’t really an option.

What mattered developmentally wasn’t the phone call itself. It was what the situation demanded. You had to tolerate discomfort. You had to read tone and pacing. You had to respond respectfully to someone who wasn’t particularly warm. You had to regulate your nerves and continue the interaction anyway.

That wasn’t just an awkward experience; it was social practice.

The same principle applies to emotionally difficult moments in adolescence.

Breaking up with someone face-to-face forces you to witness disappointment, sadness, or anger in real time. You have to manage your own emotions while responding to someone else’s. You have to repair, clarify, or at least sit with the impact of your words.

Breaking up by text or online changes that experience. It is faster. It is cleaner. And it is far less uncomfortable. But it also removes a powerful learning opportunity, the chance to stay present with another person’s emotional response.

In situations like this, the developmental cost comes from reduced emotional exposure. When discomfort is avoided, the nervous system learns less about tolerance, repair, and emotional accountability. But this is only part of the picture. In some cases, social learning is reduced because emotionally difficult interactions are avoided altogether. In other cases, even when children and adolescents do engage socially through screens, the nature of that interaction changes in another important way.

When Emotional Cues Disappear, Cognitive Load Increases

When social interaction is mediated through screens, it doesn’t become simpler; it becomes cognitively harder.

In face-to-face interaction, emotional understanding happens quickly and largely automatically. Facial expressions, tone, timing, and posture work together to guide interpretation. The brain integrates these cues with little conscious effort.

When those cues are missing, however, the brain has to work harder.

Instead of reading emotion directly, children and adolescents are forced to infer it. That inference increases cognitive load, pulling mental resources away from things like emotional regulation, perspective-taking, and thoughtful responses.

When cognitive load rises, misinterpretation becomes more likely. Ambiguity is often read as rejection or threat, especially in young people whose executive control systems are still developing. Social interaction can begin to feel exhausting, confusing, or risky because the cognitive load of interpretation has increased.

Are Kids Losing the Ability to Read Emotions?

Some emerging research suggests that children and adolescents may show reduced accuracy in reading subtle facial emotions, particularly when social interaction is limited or heavily mediated. Post-pandemic cohorts, in particular, appear to show slower recovery in social-emotional comfort during unstructured, face-to-face interaction. This doesn’t mean children are losing the capacity to read emotions; rather, it suggests they may be getting fewer opportunities to calibrate that ability through repeated, embodied social experience. The capacity remains. What’s missing is consistent practice.

Why This Feels Like a Social Skills Crisis

Social skills develop through repeated exposure to social situations and to manageable discomfort. When children and adolescents constantly avoid uncomfortable social situations (either by escaping or parents jumping in), the nervous system learns that relief comes from escape and avoidance rather than endurance. Social situations begin to feel more threatening, not because they are objectively harder, but because the system has had fewer chances to adapt and has learned that avoidance is easier.

Supporting Social Skill Development at Different Ages

Because social development unfolds in tandem with brain development, support must be age-appropriate. The goal at every stage is the same: help children stay socially engaged through manageable discomfort, without overwhelming them or removing the challenge entirely.

Early Childhood (Ages 3–6): Learning Through Co-Regulation

At this stage, children are just beginning to interpret emotions, manage impulses, and stay engaged when interaction feels uncertain.

Helpful supports:

Stay physically nearby during social play

Presence provides regulation without direct interference.Narrate emotions and intentions

“She looks surprised.”

“He’s waiting for a turn.”Normalize short social bursts

Parallel play and brief interactions are developmentally appropriate.Model repair immediately

“That didn’t work. Let’s try again.”

What matters most at this age isn’t smooth interaction; it’s exposure to emotional signals in a safe context.

Middle Childhood (Ages 7–11): Practicing Staying With Discomfort

This is when social comparison increases, and mistakes start to feel more personal.

Helpful supports:

Preview social situations

Explain what might happen and where discomfort might show up.Encourage staying slightly past the urge to quit

“Try one more minute.”Avoid solving social problems too quickly

Ask, “What do you think you could try next?”Praise effort and recovery

Not popularity or ease.

Children at this age are starting to build tolerance for awkwardness, frustration, and uncertainty. That tolerance supports later confidence.

Early Adolescence (Ages 12–14): Reducing Pressure While Increasing Exposure

During this period, social awareness intensifies, but emotional regulation is still developing. This makes social situations feel high-risk.

Helpful supports:

Lower the stakes

Small groups are better than large ones.Validate discomfort without endorsing avoidance

“Being nervous about this [experience] makes sense, and you can handle it.”Encourage face-to-face interaction in predictable settings

Shared activities reduce conversational pressure.Teach repair explicitly

Adolescents often assume mistakes are permanent.

At this stage, social withdrawal is often protective, not oppositional. The task is to keep exposure possible, not forceful.

Later Adolescence (Ages 15–18): Supporting Autonomy and Emotional Accountability

Older adolescents have more independence but still benefit from scaffolding.

Helpful supports:

Discuss the difference between comfort and growth

Help them reflect on when avoidance feels good but limits development and growth.Encourage difficult conversations in person when possible

Especially for conflict, apology, or repair.Talk openly about digital communication limits

Text is efficient, but emotionally incomplete.Model respectful disagreement and emotional ownership

This is where social skills become less about learning how to interact and more about learning when and why to stay engaged.

Across All Ages: What Matters Most

Regardless of age, social development is supported when adults:

tolerate awkwardness

resist over-rescuing

normalize emotional discomfort

model repair

protect opportunities for face-to-face interaction

For readers who want a quick reference, I’ve put together a one-page summary that outlines these age-based supports in a simple visual format. You can download it here.

Social confidence doesn’t come from avoiding hard moments; it comes from discovering, repeatedly, that hard moments are survivable.

Social skills are not disappearing, but the conditions for practicing them have changed. With the right support, however, those skills can grow again because they are a key part of human evolution and are deeply ingrained in each of us.

Kids Aren’t Losing Their Attention. They’re Getting Practice at Switching

Many parents and educators worry that children are losing their ability to focus. This article explains why attention isn’t disappearing, but adapting. Drawing on developmental psychology and cognitive science, it shows how modern environments train the brain for rapid switching rather than sustained attention — and how focus can be rebuilt through practice, not pressure.

Why Focus Is a Skill Children Can Build

One of the things I hear most often when I talk to parents and teachers is that kids don’t seem to have the capacity for sustained attention anymore.

Whether it is in classrooms, during homework, or even in conversation, many adults describe the same pattern. Kids drift quickly, lose interest faster, and seem uncomfortable staying with one thing for very long.

When we see this happening everywhere, it’s tempting to reach for a simple explanation. That’s where the familiar claim comes in: that humans now have a shorter attention span than a goldfish. Repeated often enough, it starts to sound like settled science.

It isn’t.

There is no scientific evidence showing that human attention spans have collapsed below those of a goldfish. The comparison itself does not really make sense. Attention span is not a single fixed number. It varies depending on context, motivation, emotional state, and developmental stage.

What has changed is not children’s brains.

Children today are born with the same core attention systems kids have always had. What is different is the environment those systems are developing in.

Modern childhood is filled with constant cues, rapid feedback, and endless opportunities to switch. In response, the brain adapts. Not by losing attention, but by becoming faster, more reactive, and more practiced at shifting focus.

That adaptation can look like poor attention in settings that require staying with one thing.

This is not a story about broken brains or declining children.

It is a story about practice.

And to understand what children are practicing now, we need to look at how the developing brain allocates attention.

Attention, Executive Control, and Limited Resources

Part of what supports sustained attention is something psychologists refer to as executive control.

Executive control is not about trying harder or having more discipline. It refers to the brain’s ability to allocate limited attentional resources in line with a goal, especially when there are competing demands for attention.

Research on sustained attention shows that even adults experience measurable declines in vigilance and executive control within roughly 10–15 minutes without some form of cognitive refresh. Attention does not disappear, but the capacity to sustain top-down control weakens unless the system is periodically reset.

Expecting children and adolescents to maintain continuous focus for long stretches without breaks ignores how attention actually works, especially in environments filled with competing cues.

In children and adolescents, these systems are still developing. They strengthen gradually over time and are highly sensitive to context. When the environment is filled with frequent cues, rapid feedback, and constant opportunities to switch, attentional resources are more likely to be pulled outward rather than maintained through executive regulation.

This means that when children struggle to stay focused, it is not always because they lack motivation or capacity. Often, it is because their attentional resources are being continually reallocated in response to what the environment is asking them to notice next.

The Developing Brain Was Built to Notice Change

Children’s brains are especially responsive to novelty.

From a developmental perspective, this makes sense. Young brains are designed to explore, notice differences, and update quickly based on new information. That is how learning happens.

But modern environments surround children with rapid novelty and frequent cues such as:

notifications

fast-paced media

endless options

quick feedback

Instead of getting frequent practice sustaining attention, many children get far more practice shifting it, and, over time, the brain adapts to what it repeatedly experiences.

Attention does not disappear. Control over attention shifts, becoming more reactive to external cues and less able to stay anchored when multiple demands compete for limited resources.

Focus Is Built Through Experience, Not Personality.

We often talk about attention as something children either “have” or “don’t have.”

But attention is not a single ability. It includes getting started, staying with something, shifting when needed, and returning after distraction. Many of these abilities can strengthen over time when children are given consistent opportunities to practice them in supportive conditions.

Just like muscles develop through repeated use, the ability to sustain attention develops when children regularly practice:

staying with a task past the initial excitement

working through confusion

tolerating boredom

persisting through frustration

When those opportunities are rare or constantly interrupted, attention can look weak even when a child’s underlying capacity is intact.

Why Focus Is Also an Emotional Skill

Sustained attention is not only cognitive.

It is emotional and physiological.

For kids, staying focused often means staying with feelings like:

uncertainty (“I’m not sure how to do this.”)

frustration (“This is hard.”)

boredom (“This isn’t exciting anymore.”)

self-doubt (“I’m not good at this.”)

When those feelings rise, the nervous system looks for relief. Switching tasks, grabbing a device, or disengaging reduces discomfort quickly, and the brain learns that switching works.

So when a child loses focus, it is not automatically laziness or defiance.

Often, it is emotional self-regulation. Discomfort rises, and attentional resources are reallocated as the brain reaches for relief.

Why Attention Span Feels Shorter Than It Is

If attention were a muscle, many children are training it for speed rather than for staying power. They become skilled at rapid shifts, scanning, multitasking, and responding quickly to stimulation. What they practice far less is remaining. Staying after novelty fades, after effort is required, after mistakes happen.

That is why focus can feel fragile. Not because the system is weak, but because it is being trained for something else.

Not because children cannot concentrate, but because sustained concentration requires conditions and repeated practice that are harder to find in a high-interruption world.

In today’s environments, the problem is not that children can’t focus. It’s that they are practicing a different kind of attention.

The Consequences Are Real. Even If They Are Not Permanent.

It is important to say this clearly.

The effects of chronic attentional fragmentation are not irreversible, but they are not harmless either.

Attention supports learning, emotional regulation, and social understanding. When children have fewer opportunities to practice sustained attention, there can be real downstream effects during development.

Research links reduced sustained attention to:

greater difficulty with academic learning that requires persistence

lower frustration tolerance

challenges with planning and follow-through

increased emotional reactivity when tasks feel demanding

These patterns do not mean a child is damaged or incapable.

They mean the brain has adapted to an environment that rewards speed and switching more than staying.

Development always involves trade-offs.

What we practice most becomes what we are best at.

The encouraging part is that the developing brain remains highly plastic. With the right conditions, support, and repeated experiences, the capacity for sustained attention can strengthen over time.

But that growth does not happen automatically.

It requires intentional practice.

Practical Ways to Support Sustained Attention

These are not quick fixes. Think of them as attention practice, not attention control.

1. Shrink the Time Window

Sustained attention grows through successful cycles, not long stretches.

Start with focus periods that the nervous system can realistically sustain, then pair them with brief, intentional resets.

Young children

Focus: 3–7 minutes

Refresh: 1–2 minutes

Reset ideas: movement, stretching, breathing, visual rest

Elementary-aged children

Focus: 8–15 minutes

Refresh: 2–3 minutes

Reset ideas: walking for water, posture reset, tidying the workspace

Adolescents

Focus: 15–25 minutes

Refresh: 3–5 minutes

Reset ideas: standing, short walks, brief reflection

Short, successful cycles build confidence.

Overextended demands build avoidance.

2. Make the End Visible

Attention is easier to sustain when the brain knows relief is coming.

Uncertainty increases stress and accelerates disengagement. Predictability supports regulation.

Use timers to externalize time.

Preview breaks before starting.

Say, “When this is done, we’ll stop.”

Clear endings reduce nervous system load.

3. Don’t Rescue Too Quickly

Executive control strengthens in moments of manageable difficulty.

When frustration appears, the instinct is often to remove the task. Instead:

Name the feeling.

Stay nearby.

Encourage one more attempt before switching.

This is where sustained control develops.

4. Reduce Competing Signals

Attention is a limited resource that responds to the environment.

When cues multiply, control weakens.

Silence non-essential notifications.

Close extra tabs.

Keep devices out of sight during focus periods.

This isn’t punishment.

It’s environmental support.

5. Model What Staying Looks Like

Children learn how attention works by watching adults.

Let them see you read, write, or work without constant switching.

Narrate effort, pauses, and persistence.

What’s modeled becomes normalized.

6. Praise Return, Not Perfection

Sustained attention is built through recovery, not uninterrupted focus.

Instead of praising “good focus,” praise returning.

“You noticed you were distracted and came back.”

“That was a good restart.”

Returning is the skill.

7. Build in Real Rest

Capacity grows through recovery.

Movement

Outdoor time

Unstructured play

Device-free downtime

Rest supports attention.

It doesn’t compete with it.

The Skill That Matters Most

In a world that constantly pulls attention away, the most important skill children can learn is not flawless concentration.

It is the ability to notice when attention drifts and gently bring it back.

Again.

And again.

And again.

Not because children’s brains are broken,

but because the environment has changed.

And attention, like any skill, develops through practice.

Why Digital Comparison Hits Kids So Hard

Today’s kids aren’t just comparing themselves to classmates, they’re measuring themselves against thousands of curated, filtered, and algorithmically amplified “peers.” The result is a subtle but powerful shift in how young people evaluate themselves, their progress, and their worth. This post explains why digital comparison hits kids so hard, what educators and parents are seeing, and how to help children rebuild a more grounded, resilient sense of self.

Digital life has always been described in terms of distraction, attention, or screen time. But a different psychological shift is happening under the surface, one that parents and educators are noticing even before they have the language for it.

More students hesitate to begin tasks they are capable of.

More teens downplay their own progress when it is objectively solid.

More children express worry that others are “ahead,” even when their development is exactly where it should be.

And many educators report an increase in students who seem discouraged by normal challenges or typical rates of improvement.

These patterns suggest a deeper shift in how young people evaluate themselves and how they measure where they stand. In a world saturated with curated lives and algorithmic contrast, internal standards have become harder for them to maintain.

The New Comparison Landscape

Comparison is not a flaw in human psychology; it is one of our oldest evolutionary adaptations. We evolved to evaluate ourselves within small communities where comparisons were limited, gradual, and grounded in lived experience. But today, young people are exposed to thousands of comparison points every day: academic, social, physical, creative, athletic, and aesthetic.

The scale alone changes the psychology.

Comparison used to serve as a simple calibration tool, a way of asking, “Am I on track?” Today, it has become a persistent source of inadequacy.

The question is no longer “How am I doing?”

It becomes “Why am I not doing better?”

The Psychology of Comparison: A Built-In System Under Strain

Psychologist Leon Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory explains that humans evaluate themselves by observing others. This was adaptive when social groups were small and relatively uniform. But our brains did not evolve for a world where we can compare ourselves to thousands of people who appear more successful, more attractive, more accomplished, or more socially connected.

Digital environments overload a comparison circuit designed for face-to-face, small-group living.

When comparison cues multiply faster than our ability to process them, the result is:

constant self-monitoring

chronic dissatisfaction

difficulty recognizing real progress

loss of intrinsic motivation

Kids, especially, are vulnerable to the effects of this global highlight reel when evaluating local progress.

Upward Comparison: Why Digital Feeds Skew Negative

On social platforms, people rarely show ordinary moments. Instead, they display:

achievements

curated bodies

filtered faces

milestones

polished routines

highlight reels

Research consistently shows that upward comparison, comparing ourselves to someone “doing better,” is the most common type of comparison online.

Upward comparison is intensified online because digital platforms surface peak achievements, idealized images, and curated successes. For adolescents, this comparison is particularly powerful; their reward systems are highly sensitive to social feedback, and their sense of competence is still consolidating.

In practice, a teenager is not comparing themselves to the small group of peers they see daily.

They are simultaneously comparing themselves to the top performers in every domain of life.

From this, a consistent pattern emerges:

lowered mood

increased self-criticism

distorted expectations

heightened academic pressure

social anxiety

reduced satisfaction with one’s own life

Algorithmic Amplification: Why Comparison Is Unavoidable

If humans were simply comparing themselves to people online, the psychological effects would be significant but manageable. What changes everything is the role of algorithms.

Algorithms do not show a representative sample of life. They show what drives engagement: the most extreme, polished, emotionally charged, or aspirational content.

This means that digital environments:

magnify contrast

intensify upward comparison

reduce exposure to normal, average, or realistic peers

The algorithm becomes a comparison accelerator, turning natural social evaluation into a constant and exaggerated cognitive load that developing minds interpret as truth.

Self-Discrepancy Theory: The Expanding Gap Between Selves

Psychologist E. Tory Higgins described three important versions of the self:

Actual self: the attributes you believe you possess

Ideal self: the attributes you wish you possessed (hopes and aspirations)

Ought self: the attributes you believe you should possess (duties and obligations)

Digital contrast widens the gap between these selves dramatically.

The more idealized content kids see, the more impossible their ideal self becomes.

The more polished peer achievements they observe, the heavier the ought self feels.

The more they compare their ordinary lives to curated feeds, the smaller the actual self seems.

This widening gap produces:

anxiety

shame

avoidance

perfectionism

reduced motivation

emotional exhaustion

Kids feel as though they are constantly falling short of an invisible standard.

Competence and Motivation: How Comparison Erodes Self-Belief

Self-efficacy, as Bandura described, is the belief in one’s ability to succeed. It is built through mastery, practice, and real progress.

Comparison disrupts this mechanism.

When kids see peers, or even strangers online, who appear far ahead of them academically, socially, physically, or creatively, their sense of expectancy begins to erode. Expectancy is the belief that “I can improve,” and it is one of the strongest predictors of motivation.

But comparison affects more than expectancy. It also affects value, the belief that something is worth doing. Expectancy–Value Theory shows that children are motivated when they believe they can succeed and believe the task matters.

Digital comparison distorts both.

When expectancy falls, kids think:

“I’ll never catch up.”

“Everyone else is already better.”

“Why try if I’m so far behind?”

When value falls, kids think:

“Even if I improve, it won’t matter.”

“My accomplishments are tiny compared to theirs.”

“This doesn’t feel meaningful anymore.”

Together, lowered expectancy and lowered value lead to:

Lower persistence: Normal difficulty feels like proof of inadequacy, so kids give up sooner.

Fear of failure: Comparison raises the stakes of making mistakes. Kids avoid risks because a misstep feels like public confirmation that they are “behind.”

Avoidance of challenges: Tasks that once felt appropriately difficult now feel threatening. If success seems unlikely, it becomes safer not to try at all.

Decreased willingness to try new things: New activities require vulnerability and a beginner mindset. In a comparison-saturated environment, kids worry that being “bad at first” will make the gap feel even wider

“What’s the point?” thinking: When both expectancy (“Can I do this?”) and value (“Is this worth it?”) fall, motivation collapses. The effort required feels too high, and the potential reward feels too small.

Kids stop trying not because they lack potential, but because the digital comparison landscape makes their efforts feel small, slow, or insignificant. The very systems that once built competence now undermine it by continuously resetting expectations to unrealistic levels.

The Comparison Loop: A Habit the Brain Learns

With enough repetition, comparison becomes automatic. Kids and adults begin:

checking feeds reflexively

evaluating themselves before posting

adjusting behavior based on imagined reactions

scanning for rank rather than connection

Over time, the mind becomes comparison-oriented, a cognitive habit that influences self-worth even offline.

This is not an identity shift; it is a thinking style shift.

And it is one that digital environments reinforce every day.

AI and the Comparison Multiplier

AI-enhanced imagery and generative content escalate comparison further. Where social media once showed curated lives, AI now shows impossible ones:

flawless skin

perfect symmetry

aesthetic routines

optimized daily schedules

unrealistic productivity

idealized bodies

These are not just unrealistic. They are unhuman.

The result is a widening self-discrepancy gap and a tightening comparison loop.

AI does for standards what algorithms did for visibility:

It pushes them past the threshold of what is achievable.

What Parents and Educators Are Seeing

The Comparison Effect shows up long before kids can explain what they are feeling. Adults often notice patterns like these:

Students feeling “behind” academically

Even when their performance matches developmental expectations, students compare themselves to top-performing peers or polished content online, leading to unnecessary stress and self-doubt.Teens are reluctant to try new things

Trying something new requires being a beginner, but comparison makes “starting from zero” feel embarrassing or risky. Teens avoid new activities to protect their self-image.Increased perfectionism and meltdown cycles

When the internal standard is impossible to meet, even small imperfections can feel like failures. This often leads to frustration, emotional overload, or abandoning the task entirely.Preoccupation with peer performance

Students frequently monitor what classmates achieve, grades, sports results, and social milestones, and use these as benchmarks for their own worth or progress.Anxiety around posting or participating

The fear of judgment grows when kids expect their performance to be compared or evaluated instantly, whether in class discussions, group work, or online spaces.More quitting before starting

If effort seems unlikely to “catch up” to the perceived level of others, students disengage early to avoid the discomfort of feeling behind.Chronic discouragement

Continual upward comparison erodes confidence. Kids who once showed enthusiasm begin to anticipate disappointment before they even begin.Difficulty accepting “good enough.”

When the comparison field is filled with ideal outcomes, anything short of perfection feels inadequate. Kids struggle to recognize healthy progress or reasonable expectations.

These patterns are not failures of character. They are predictable responses to environments that distort evaluation, amplify contrast, and make ordinary progress feel inadequate.

Recalibrating the Mind: The Four R’s of Healthier Comparison

The goal is not to eliminate comparison entirely. Comparison can motivate, orient, and guide us when it is grounded in reality. The challenge is helping young people regulate how often they compare, what they compare to, and how they interpret contrast.

These four practices can help recalibrate the comparison system so it becomes supportive rather than overwhelming.

1. Reduce

Lower the volume of comparison inputs.

Unfollow accounts that consistently trigger self-doubt or inadequacy.

Many comparison spirals begin with a small number of highly curated or extreme exemplars.Move high-use apps off the home screen.

Even one extra tap reduces reflexive checking and lowers automatic comparison loops.Disable “suggested” or algorithm-driven feeds when possible.

Algorithmic content disproportionately features idealized routines, achievements, or aesthetics, which tend to be the most potent comparison triggers.Limit exposure to extreme outliers.

Kids don’t need constant visibility of the “top 1%” of any domain; it distorts what typical progress looks like.

Reducing input creates cognitive space for more accurate self-evaluation.

2. Replace

Substitute comparison triggers with healthier reference points.

Follow creators who show process, not just outcomes.

Seeing practice, mistakes, and gradual growth provides more realistic models of progress.Seek out “real day in the life” content.

These depictions often show routines, setbacks, downtime, and normal variability.Encourage peer comparison based on effort or improvement, not rank.

“Who improved?” is a healthier metric than “Who is best?”Use progress journals instead of performance metrics.

Tracking one’s own growth reduces the tendency to measure success against others.

Replacing unrealistic standards with grounded, human examples reshapes how contrast is interpreted.

3. Recalibrate

Realign internal standards with reality rather than digital exaggeration.

Spend regular time in unfiltered environments.

Grocery stores, parks, classrooms, community events, anywhere where real diversity in appearance, ability, and behavior is visible.Discuss curation openly at home or school.

Kids benefit enormously when adults explain that online content is selective, edited, and strategically presented.Normalize imperfection and slow progress.

Many children have never seen adults struggle through something difficult. Seeing authentic effort recalibrates expectations.Celebrate small wins that aren’t visible online.

Consistency, problem-solving, kindness, and persistence rarely make it into social feeds but matter deeply for development.

Recalibration restores a realistic sense of what “normal” looks and feels like.

4. Rebuild

Strengthen the internal systems that counteract comparison pressure.

Focus on mastery through hands-on tasks.

Cooking, building, learning an instrument, or sports practice give kids tangible evidence of improvement.Break goals into manageable steps.

When progress is visible and achievable, expectancy rises, and comparison loses its power.Help kids track their own improvement over time.

Self-referenced progress reduces the influence of external benchmarks.Reinforce self-efficacy by praising effort, strategy, and persistence.

This shifts motivation away from external comparison and toward internal competence.

Rebuilding gives young people the psychological tools to evaluate themselves accurately, even in comparison-heavy environments.

Practical Tools for Parents and Educators

These strategies help shift evaluation from external comparison to internal growth. They work in classrooms, families, counseling settings, and extracurricular programs.

Try introducing:

A weekly comparison audit.

Invite kids to reflect on the moments during the week when they felt behind or inadequate.

Prompts might include:

“When did I compare myself to someone else?”

“What triggered it?”

“Was the comparison realistic or curated?”

“What would be a fairer benchmark?”

This builds awareness of comparison patterns and helps students interrupt automatic self-judgment.

Classroom discussions about curated content

Use age-appropriate examples of edited photos, highlight reels, AI-altered images, or exaggerated success stories.

Discuss with students:

What gets posted vs. what doesn’t

How algorithms amplify extreme examples

The difference between process and performance

How to spot unrealistic portrayals

These conversations normalize the idea that online content is selective, not representative.

Peer circles that share progress, not performance

Structure small groups where students talk about what they worked on, what felt challenging, and what improved, and not who got the highest score or best result.

This emphasizes:

effort

learning curves

persistence

strategies that worked

It replaces rank-based comparison with collaborative growth.

Reflective prompts such as “What did you get better at this week?”

A simple five-minute routine that helps kids notice their own improvement.

Other effective prompts:

“What was one small win?”

“What challenged me and how did I respond?”

“Where did I see progress I might have missed?”

“What am I proud of that no one else sees?”

This strengthens internal evaluation and counters “I’m behind” thinking.

Strength mapping exercises

Have students identify and track their strengths over time.

Examples:

creating a personal “strength profile”

mapping strengths to new challenges (“How could patience help me with math?”)

updating strengths quarterly to show growth

Strength mapping builds self-awareness and expands the range of qualities students value in themselves.

“Good enough” routines that counter perfectionism

Establish small practices that normalize imperfection and reduce pressure.

Examples:

“first draft Fridays” where drafts are shared even when imperfect

“messy minutes” where students try something new with no expectation of success

teachers modeling unfinished work and talking about their own learning process

families celebrating effort-based achievements at dinner

This helps kids see that progress, not perfection, is the goal.

A Return to Intrinsic Standards

The Comparison Effect is not about identity loss. It is about evaluation overload. When young people are exposed to more contrast than the developing mind can process, self-worth becomes reactive, unstable, and externally defined.

But comparison is not the enemy. Unregulated comparison is.

With awareness, structure, and intentional habits, we can help kids and ourselves reclaim a grounded sense of capability.

Not by eliminating comparison, but by recalibrating it.

By teaching young people to measure themselves not against a global highlight reel, but against who they were yesterday.

Identity Drift: How Digital Spaces Reshape Who We Think We Are

Identity Drift is the subtle psychological shift that happens when our sense of self becomes shaped more by digital signals than real experiences.

From curated feeds to algorithmic mirrors, social media can quietly pull our identity away from who we are and toward who we think we should be.

This post explores how—and how to reclaim a grounded, stable sense of self in a digital world.

Digital life is changing how we focus and how we feel. It is also changing something deeper, our sense of who we are. Psychologists have long argued that identity is not a fixed trait. It is shaped by the environments we move through and the feedback we receive. Today, those environments and feedback loops are increasingly digital rather than physical.

If you have ever asked yourself:

“Why do I feel behind, even when things are fine?”

“Why do I lose confidence after scrolling?”

“Why do I feel less certain, even when nothing has changed?”

You are experiencing what I call Identity Drift.

This happens because the foundations of identity, such as competence, comparison, belonging, and self-reflection, have migrated from real, lived experiences to digital platforms that distort them. Identity does not disappear. It becomes untethered from the physical world and increasingly anchored in the digital one.

Identity Used to Be Slow Work, and Digital Life Made It Fast

For most of human history, identity developed through experience. We learned who we were by trying things, practicing them, making mistakes, contributing to our communities, and receiving feedback with real social meaning.

This process builds what Albert Bandura called self-efficacy, the belief in our ability to manage challenges because we have evidence that we can. Research consistently shows that self-efficacy is built through mastery experiences, not compliments or encouragement alone. Identity grows stronger when it is rooted in real capability.

Digital environments introduce a shortcut. Instead of building confidence through practice, we can generate the appearance of confidence instantly. A well-lit photo, a boost in likes, a polished profile, or a viral moment can feel like an accomplishment without the corresponding effort. Psychologists often describe this as contingent self-esteem, a fragile sense of worth tied to external approval.

This is the first mechanism of Identity Drift. The signals that once reflected our identity now begin to shape it.

The Highlight Reel Problem, When Curated Lives Become the Standard

Once our accomplishments become performative, the next force shaping identity is comparison. Decades of research show that humans engage in social comparison automatically. We assess how we are doing by looking at the people around us. Offline, those comparison groups were limited to peers, coworkers, neighbors, classmates, and family.

Online, that comparison pool expands to thousands of people, most of whom we know only through their edited moments. Studies on social media and mental health consistently show that curated content increases anxiety, lowers mood, and reduces self-esteem because the brain treats these snapshots as real reference points. Even when we know intellectually that photos are curated, our emotional systems respond as if they are representative.

We end up comparing our full, unfiltered lives to everyone else’s most impressive moments. Researchers call this upward social comparison, and it is one of the strongest predictors of decreased well-being in digital contexts.